News is slowly seeping its way into the press regarding the incredible discovery and excavation of the SS City of Cairo, a World War II British Merchant Navy vessel sunk in the South Atlantic at the height of the Battle of the Atlantic. The stories surrounding the City of Cairo are numerous with an entire book, Goodnight, Sorry for Sinking You, having been written about her sinking and the travails of her survivors. The City of Cairo was traveling from Bombay, India to the UK with stopovers in South Africa and Brazil and among her cargo of 7,422 tons were 2,000 boxes of silver Indian rupees stowed in the Number 4 hold.

In addition to the general cargo and precious metals, the City of Cairo carried 150 passengers with a total complement of 311 souls aboard. Sighted by U-68, a German U-boat captained by Karl-Friedrich Merten, the City of Cairo was quickly dispatched on the night of November 6, 1942 by two torpedoes. Six lives were lost in the initial evacuation into six overcrowded lifeboats. Interested in learning what vessel he had sunk and what she was carrying, Merten surfaced his U-boat to speak with the survivors. He directed them to the closest land and closed with the now semi-famous words, “Goodnight, sorry for sinking you.”

The survivors then began what would become an epic and tragic fight for survival. Unfortunately, the boats rapidly lost touch with one another in the vastness of the South Atlantic. One group consisting of three boats with 155 survivors was picked up on November 19th after thirteen harrowing days at sea. The group had nearly made it to their destination of St. Helena which was 500 miles from the point of sinking. Another group of only 2 survivors was picked up on December 27th only 80 miles from the coast of Brazil. The original group of 17 had sailed nearly 2,000 miles before being rescued. The third group of three survivors were rescued by a German blockade runner, Rhakotis on December 12th. One of the survivors perished aboard the Rhakotis. For the two survivors, their story became even stranger when, on January 1, the Rhakotis was herself intercepted and sunk by Allied warships. Thankfully, the two were rescued and brought home safely to the United Kingdom. In all, 104 persons died as a result of the sinking.

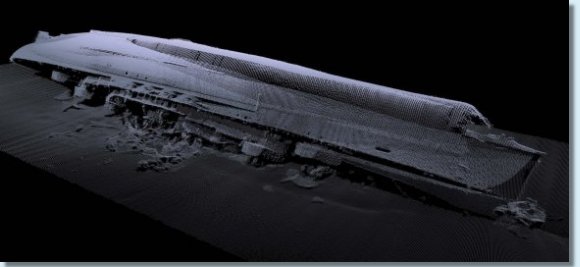

Public information is very limited as the salvors have sought a low profile with the project, but the salvage company Deep Ocean Search is claiming to have recovered 100 tons of silver coins from the wreck of the City of Cairo over the last few years. If true, then it is quite an accomplishment as the wreck lay in 17,000 feet of water and days of sailing from the closest port. The photos of the wreck and coins provided by Deep Ocean Search are quite stunning. There has been no word on whether the company intends to make the coins available for sale or is melting them for sale into the precious metals market.

Today marks the 28th anniversary of the sinking of the Peruvian Navy submarine Pacocha which was lost off the Peruvian port of Callao near Lima. Running on the surface on the night of August 26th, 1988, the Pacocha was accidentally rammed by a Japanese fishing trawler. Mistaking the conning tower of the sub for a small craft and thinking the two craft would pass one another harmlessly, the trawler’s crew did not take evasive action and the trawler struck the sub’s hull. The Pacocha‘s captain, Captain Daniel Nieva and six crew members were killed immediately while twenty-two sailors were able to successfully abandon ship. The United States immediately dispatched an underwater rescue team, however, the Peruvians quickly deployed a diving bell and, within 24 hours, gained access to the sub’s trapped crew through one of the Pacocha‘s hatches. The remaining twenty-three crew were safely brought to the surface, escaping an excruciating death of painful asphyxiation from chloride gas or drowning as the sub’s remaining compartments slowly filled with water.

Today marks the 28th anniversary of the sinking of the Peruvian Navy submarine Pacocha which was lost off the Peruvian port of Callao near Lima. Running on the surface on the night of August 26th, 1988, the Pacocha was accidentally rammed by a Japanese fishing trawler. Mistaking the conning tower of the sub for a small craft and thinking the two craft would pass one another harmlessly, the trawler’s crew did not take evasive action and the trawler struck the sub’s hull. The Pacocha‘s captain, Captain Daniel Nieva and six crew members were killed immediately while twenty-two sailors were able to successfully abandon ship. The United States immediately dispatched an underwater rescue team, however, the Peruvians quickly deployed a diving bell and, within 24 hours, gained access to the sub’s trapped crew through one of the Pacocha‘s hatches. The remaining twenty-three crew were safely brought to the surface, escaping an excruciating death of painful asphyxiation from chloride gas or drowning as the sub’s remaining compartments slowly filled with water.