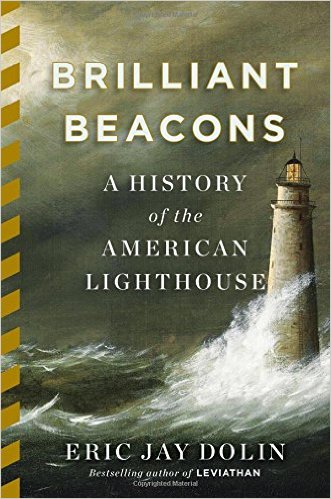

Eric Jay Dolin, whose previous work includes Leviathan and When America Met China, has generated yet another meticulously researched and well narrated piece of nautical history. Focusing on America’s lighthouses from inception to the current day, Brilliant Beacons is a sweeping, majestic piece that encompasses technology, material culture, engineering, personal histories and the strategic role lighthouses have played in America’s development and growth over the last three plus centuries.

Writing with the passion of someone who has long had a love affair with the sea and her incredible stories, Dolin draws the reader in with the origins of American lighthouse design and tirelessly waltzes through topics that lesser authors would render dry and boring. This is the second of Dolin’s books reviewed on this site and both have held particular meaning for me. The first being When America Met China, which, for someone who majored in Chinese language at America’s ninth oldest university, was of particular interest and is a phenomenal read. Having grown up in North Carolina, I have always had an affinity for lighthouses, especially given that I was a young teenager when the iconic Cape Hatteras light house was moved 1,500 feet to save it from being engulfed by the ravaging waves of the Atlantic. Thus, the subject of Brilliant Beacons more than intrigued me and, while I didn’t have the opportunity to read it at the beach, I read the first 25% from my home overlooking the Port of Tampa and the remaining 75% on a round-trip flight to New York City, a city forever linked with the sea.

Overall, Dolin’s narrative style enables the reader to make quick work of the book’s 400 plus pages. Saying Brilliant Beacons is the perfect beach read might sound a little cliche, however, the book is both illuminating and entertaining and the timing of its release at the height of the summer months could not have been better planned. Pick up Dolin’s latest and read away, you will be glad you did.