Operation Storm by John J. Geoghegan relates the obscure story of Japan’s last ditch effort to launch an attack on American soil in the closing days of World War II. Geoghegan, the executive director of The SILOE Research Institute’s Archival Division, devotes much of his writing to white elephant technology and thus his choice of subject matter is quite apropos. Over the course of ~400 pages, Geoghegan introduces the reader to the Japanese naval officers and designers who helped craft a Hail Mary strategy of launching an airstrike on the Panama Canal from the largest submarines of the war. Each submarine was designed as an underwater aircraft carrier to carry two or three specially developed strike aircraft and the path of their development makes for incredible reading.

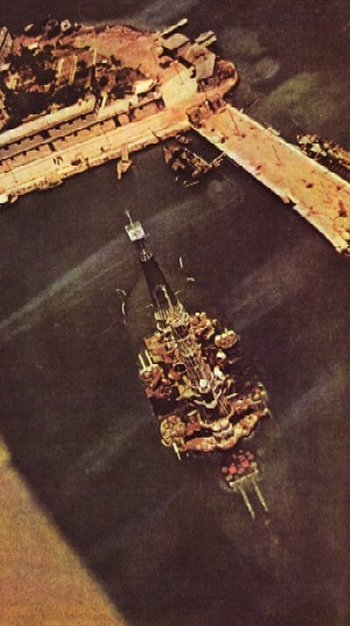

Geoghegan also tells the backstory of the USS Segundo (a sub that often operated in conjunction with USS Razorback) which captured one of the subs in the uneasy days following the capitulation of Japan. Relying on extensive archival research as well as interviews with survivors of the Japanese program, Geoghegan provides readers with a highly readable account of this overlooked aspect of World War II history. In addition to the strength of his research, Geoghegan integrates the story into the continued development of America’s submarine program in the years following World War II. Finally, readers are brought full circle to the present day via two modern points of reference. First, one of the subs (I-401) was re-discovered in 2005 off the coast of Hawaii where it had been used for torpedo practice by the US Navy after the war. Second, the Smithsonian Institution displays the only surviving example of the subs’ Seiran attack planes at its spectacular Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in northern Virginia near Dulles Airport. Operation Storm is highly recommended for anyone interested in obscure technology, warfare or a non-traditional history of World War II.