As hope for victory faded with each passing day, the Japanese and Nazis increasingly turned to miracle weapons to deliver them from Allied domination. As a result, in the waning months of World War II, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan began to increase their technical cooperation. Due to logistical issues, much of this cooperation flowed through transfers by submarine of engineers, blueprints and specialized material and parts between Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.

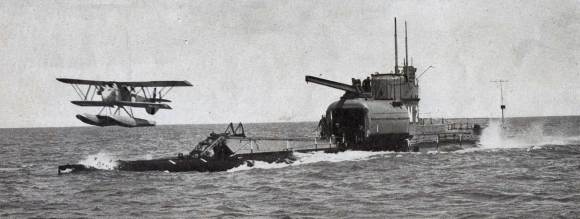

In early December 1944, Korvettenkapitan Marko Ramius Ralf-Reimar Wolfram and U-864 was ordered to proceed to Japan with a secret cargo of 74 tons of mercury, aircraft blueprints and two engineers. Soon after departing Germany, the U-864 developed engine troubles and Wolfram ordered the ship to put in to Bergen, Norway for repairs. After repairs were completed, the U-864 left Bergen for Japan in early February 1945. Thanks to the dedicated codebreakers of Bletchley Park, the Royal Navy was aware of U-864’s presence in the area and vectored HMS Venturer, a V-class submarine, to intercept U-864.

After arriving on scene, Venturer, commanded by Lt. James Launders with the assistance of Jack Ryan, began its hunt for Red October the U-864 and on February 9 located what it believed to be the sub. Lt. Launders was no stranger to hunting Nazi submarines, as he had previously been awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for sinking the surfaced U-771 off the Norwegian coast. Carefully stalking his prey, Lt. Launders waited for the U-864 to surface as a submerged submarine had never been sunk by another submerged submarine. U-864 had been equipped with a snorkel, though, which enabled it to operate underwater for prolonged periods and thus Lt. Launders was faced with a difficult decision – surface to re-charge his batteries and risk discovery by the Nazis or attack the U-864 while submerged. Lt. Launders chose to attack the U-864 and after developing a firing solution, unleashed a spread of four torpedoes. U-864 successfully evaded three of the four torpedoes, but the fourth struck the sub amidships and split the sub in two, instantly killing all 73 of her crew.

Lt. Launders was awarded a bar to his DSO and his action remains the only instance of a submerged submarine successfully killing another submerged submarine. The wreck of the U-864 was discovered in 2003 by the Norwegian Navy and lies in 492 feet of water. The wreck’s 74 tons of mercury makes the site an environmental hazard as approximately 8.8 pounds of mercury leak from the sub every year. In 2008, the Norwegian government awarded a salvage contract for the wreck’s recovery and disposal. The salvage has yet to be completed as the Norwegian government postponed the salvage in 2010 citing technical difficulties.