Israel’s elite Mossad and commando forces are well known for their daring operations such as the Raid on Entebbe and the snatching of Adolf Eichmann

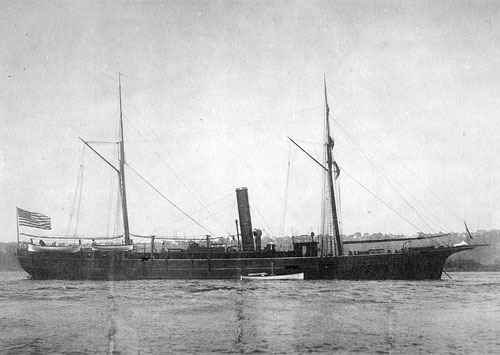

from Argentina. Less well known, though, are the naval commandos of Shayetet 13 who scored their first major victory on October 22, 1948. As a cease-fire loomed between Israel and Egypt, the Israeli Navy identified an opportunity to destroy the flagship of the Egyptian Navy – the King Farouk. Built on the River Clyde in Great Britain the King Farouk had spent ten years as a passenger ship before being converted into a warship in 1936 for the Egyptian Navy.

Lacking the resources and time to build a traditional blue-water navy, the Israelis decided to create a small group of special forces capable of pinpoint attacks. This force, which later became Shayetet 13, procured explosive motorboats from the Italian Navy. The boats had been developed for Italy’s highly successful frogmen during World War Two and were an off-the-shelf solution to creating an Israeli navy from thin air. Designed to explode upon impact, the boats would be vectored to their target by commandos who would abandon ship just prior to detonation. After only a few months of training, the commandos were thrust onto center stage as the King Farouk and an Egyptian minesweeper sailed into waters where the ships were particularly vulnerable to attack.

After heated internal debate about whether or not to attack with the ceasefire agreement looming, the Israeli mother ship was ordered to a point where it could release the small craft. After a short sprint down the Gaza coastline, the Israeli assault boats began their attack on the King Farouk and the accompanying minesweeper. Both ships were successfully struck and within five minutes the King Farouk was lying on the bottom of the Mediterranean. Although not widely publicized at the time, the sinking of the King Farouk and crippling of her accompanying minesweeper put the Arab world on notice that the Israeli Navy was a force to be reckoned with.