Today marks the tenth anniversary of the capsizing of the Sengalese ship, M/V Le Joola, on September 26, 2002. Le Joola was a government owned roll-on, roll-off ferry which operated between Senegalese ports on the Atlantic Ocean. At the time of its sinking, ferry travel was a popular option because a civil war made the land route prohibitively dangerous. The ferry’s maximum capacity was approximately 550, however, there were nearly 2,000 passengers aboard the ship when it capsized 35 kilometers off the Gambian coast.

A combination of overcrowding and gross neglect (the ship had only recently returned to service after a multi-year hiatus) contributed to the ship’s capsizing although the exact cause of the sinking has never been conclusively proven. It was also alleged that political considerations regarding the appeasement of separatist groups within Senegal encouraged the Senegalese government to return the ferry to service before it was fully seaworthy.

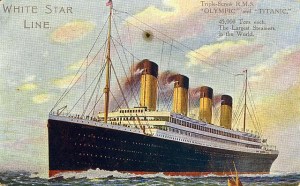

Sadly, only ~60 of the nearly 2,000 souls aboard survived and an exact body count has never been determined. The disaster is one of the worst sinkings in history with more lives lost than that of RMS Titanic, however it pales in comparison to the ~9,000 lives lost aboard the M/V Wilhelm Gustloff in 1945. The ship’s sinking continues to have ramifications today with survivors and victims’ families demanding a new inquiry into the causes of the sinking.